Introduction:

When precision molds crack prematurely or medical parts fail inspection, the culprit is often hidden within the steel itself—not your machining process. While 1.2316 steel is the industry standard for corrosion resistance and high polishability, there is a massive gap between ‘premium’ and ‘common’ market grades. The difference comes down to how strictly mills control three specific metallurgical defects: carbide segregation, inclusions, and grain size. Understanding these hidden flaws is the only way to secure steady performance and avoid expensive downtime.

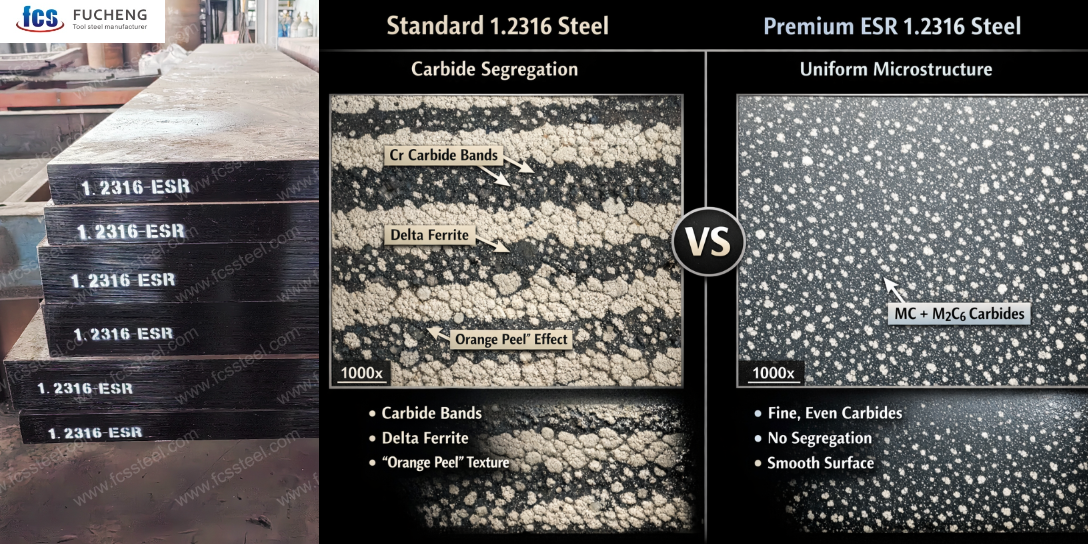

Defect 1: Carbide Segregation & “Orange Peel” in 1.2316 Steel

Standard 1.2316 often suffers from carbide segregation, creating alternating bands of soft delta ferrite and hard chromium carbides. During high-gloss polishing, these zones wear at different rates. The soft areas erode quickly while the hard bands resist, creating a wavy, bumpy texture known as “Orange Peel.” No matter how skilled your polisher is, you cannot achieve a true mirror finish on segregated steel. This defect usually appears only at the final stage, wasting days of machining time on a mold that will never meet optical standards.

Why Carbide Banding Destroys Optical Finishes

China’s GB/T 6402-2008 standard groups carbide defects by size:

| Class | Fine Size | Coarse Size |

|---|---|---|

| B | 0.5 mm | 0.5 mm |

| C | 1.0 mm | 1.0 mm |

| D | 1.5 mm | 1.0 mm |

Chemistry Behind Carbide Formation:

The chemical makeup of 1.2316 forms carbides during cooling:

- Carbon (0.33-0.45 wt%): Combines with chromium to form M23C6 carbides

- Chromium (15.5-17.5 wt%): Main carbide-forming element

- Molybdenum (0.8-1.3 wt%): Forms both M23C6 and MC carbides

- Manganese (≤1.5 wt%) and Silicon (≤1.0 wt%): Minor contributors

M23C6 carbide formation peaks at 0.18 wt% carbon content. It then drops above 0.30 wt%. These carbides look like short rod-like structures. They measure 20-100 nanometers in well-processed steel. In segregated material, they cluster into thick bands.

MC carbides stay smaller—under 20 nanometers. They appear spherical. Their formation depends on vanadium content.

Solution: Eliminating Segregation via ESR Technology

Electroslag remelting (ESR) stops carbide clustering. It uses rapid controlled cooling. The process spreads carbides evenly across the entire steel. No clumping. No bands. No soft-hard zone variations.Look at the hardness measurements:

| Feature | Standard 1.2316 | Premium ESR 1.2316 | Customer Impact |

| Microstructure | Carbide Banding & Clusters | Uniform Distribution | Prevents “Orange Peel” during polishing |

| Hardness Consistency | ±2-3 HRC swings | ±1 HRC max (Surface to Core) | Stable machining and zero soft spots |

| Corrosion Resistance | Rust within 48 hours | 60+ Hours (Humidity Test) | Superior resistance to PVC hydrochloric acid |

| PVC Mold Life | 120k – 150k Cycles | 200,000+ Cycles | Reduces downtime and re-polishing costs |

| Carbide Class | Class B to D (GB/T 6402) | Class A (≤0.25 mm) | Lower stress points; prevents premature cracking |

“In high-chromium steels like 1.2316, the primary challenge is the formation of massive primary carbides during ingot solidification. Without subsequent Electroslag Remelting (ESR), these carbides form clusters that are significantly harder than the surrounding matrix, making it physically impossible to achieve a uniform mirror finish.” — George Roberts, Former President of ASM International.

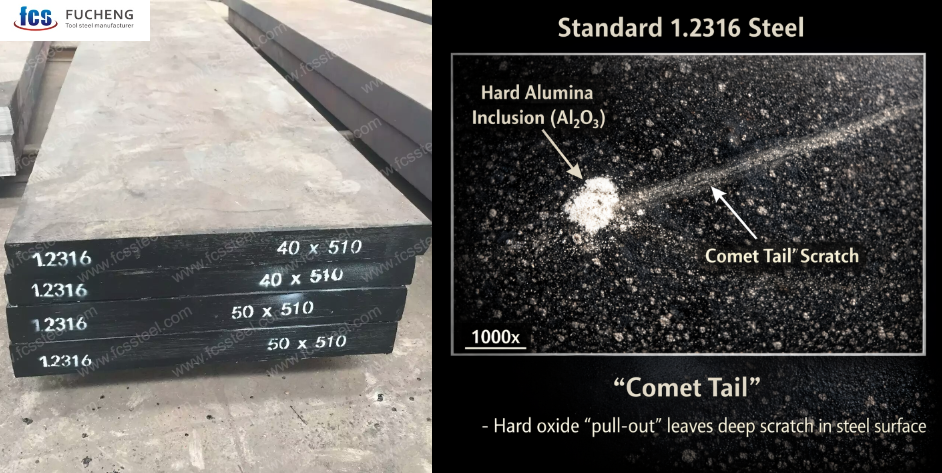

Defect 2: Non-Metallic Inclusions & “Comet Tail” Pitting

Tiny particles trapped inside steel cause more failures than most buyers think. These non-metallic bits act like dirt stuck in the material. They create weak spots. They ruin polishing results. They cause early cracking.

These inclusions form during melting and cooling. Oxides, sulfides, and silicates get trapped in the steel. Even small amounts hurt the material’s strength. Top mills control these particles through multiple refining steps and careful testing.

Measuring Inclusion Cleanliness Standards

ASTM E45 Method A sets the standard for measuring these inclusions. This test checks four types:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Type A (Sulfides) | Long gray particles |

| Type B (Alumina) | Grouped oxide strings |

| Type C (Silicates) | Random scattered bits |

| Type D (Globular Oxides) | Round, separate particles |

Premium ESR 1.2316 achieves ratings of ≤1.0 for thick inclusions and ≤1.5 for thin inclusions. Standard melted material often scores 2.0-3.0 or higher. Each full point increase doubles the risk of surface defects during polishing.

Case Study: The High Cost of “Dirty” Steel in Polishing

The numbers in ASTM E45 charts might seem abstract, but their impact on the shop floor is brutal. The most common failure in standard 1.2316 steel is the “pull-out” effect during high-gloss polishing.

Imagine a technician reaching the final stage using 3-micron diamond paste. Suddenly, tiny pits appear on the mirror finish. This happens because hard alumina inclusions (Type B) don’t bond well with the steel matrix. The polishing cloth rips these hard particles out of the surface, leaving a void behind.

Worse yet, the loose particle gets trapped in the polishing pad. It gets dragged across the pristine surface, cutting a deep scratch that looks like a meteor with a tail—industry veterans call this a “Comet Tail.”

The Cost of “Dirty” Steel:

Endless Rework: You have to regrind the surface down by 0.02-0.05mm to clear the pit, adding 10+ hours of manual labor.

Total Scrap Risk: In segregation-heavy steel, inclusions often come in clusters. Grinding deeper just reveals more pits, eventually making the mold insert unusable.

“A ‘Comet Tail’ is not a polishing error; it is a microscopic excavation. When hard alumina (Al₂O₃) particles are dislodged from a relatively soft steel matrix, they act as uncontrolled abrasives. In medical-grade 1.2316, we strictly limit Type B inclusions to less than 0.5 because even a single cluster can ruin an optical-grade mold insert worth $20,000.” — Technical Manager at a Leading European Specialty Steel Mill.

Prevention: Demanding Low-Sulfur LF+VD+ESR Processing

The melting steps decide final cleanliness. Top mills use this four-stage process:

IM/EAF (Initial Melting) → LF (Ladle Furnace Refining) → VD (Vacuum Degassing) → ESR (Electroslag Remelting)

Each stage removes different pollutants:

LF refining: Drops phosphorus and sulfur to ≤0.030% each (compared to ≤0.045% in basic grades)

VD treatment: Pulls out dissolved gases. Cuts down oxide formation.

ESR processing: Filters leftover inclusions through molten slag. This achieves the highest purity level.

Mills that skip VD or ESR stages make material with 3-5 times more inclusions. You’ll spot this during polishing—pits and scratches show up where inclusions pull out from the surface.

Mechanical Processing Controls Inclusion Distribution

Forging reduction ratio matters. Premium suppliers keep minimum 5:1 reduction ratios during hot working. This means shrinking the ingot cross-section to one-fifth its original size through forging.

Higher reduction ratios break up and spread out inclusions. They stop clustering. Material with poor reduction (below 3:1) shows inclusion banding—tight lines of particles that weaken certain areas.

Grain size checks through ASTM E112 testing confirm proper processing. ESR 1.2316 achieves grain size ≥6.0. This shows fine, even grain structure. This structure links to lower inclusion density and better mechanical properties.

Detection Methods for Hidden Defects

Visual checks miss most inclusions. Pro mills use multiple detection systems:

Ultrasonic Testing Standards:

– SEP1921 (German standard, most strict)

– EN 10308 (European spec)

– ASTM A388 (American standard)

These ultrasonic methods find internal inclusions down to 0.5mm across. Sound waves bounce off density changes caused by non-metallic particles. Trained technicians map inclusion spots and sizes throughout the entire billet.

Macro-structure testing (ASTM E381) checks inclusion spread patterns through acid etching. This shows centerline buildup, surface loss of carbon, and inclusion clusters you can’t see otherwise.

Defect 3: Coarse Grain Size & Heat Treatment Failures

Heat treatment failures? Check the grain structure first. You can’t see it without tools. 1.2316 steel with uneven grain size hardens unpredictably. Parts from one batch act different during quench and temper. You get warping, soft spots, and hardness that varies too much. This kills precision tooling.

Top mills control grain structure tight. They use strict forging ratios and heat schedules. The result? Heat treatment works the same every time. Standard material with bad grain control? You’ll waste time and money on trial runs.

The Link Between ASTM E112 Grain Score and Cracking

ASTM E112 testing uses numbers to measure grain structure. Grain size ≥6.0 is the minimum for quality 1.2316 steel. Premium grades hit grain size 5-8 range. That means finer, more even grains all through the steel.

Why care about this number? Finer grains give you:

- Even hardness after quench (±1 HRC difference vs. ±3 HRC in coarse-grain stuff)

- Better size stability during heat treatment (under 0.15% warping)

- Better toughness without losing hardness

Coarse grain structure (below size 5) makes big austenite zones during heating. These zones change at different rates during cooling. You get hard martensite spots mixed with softer bainite spots. This mixed structure wrecks tool performance.

Master’s Rule: “In 20 years, I’ve seen it: if your 1.2316 isn’t ASTM 6+, you’re gambling. One mold warps 0.2mm, the other stays at 0.02mm. It’s not the heat treater—it’s the steel’s ‘DNA’ creating a tug-of-war during quenching. If the structure is messy, no technician can save it.”

Prevention: Ensuring 5:1 Forging Ratio for Fine Grain Structure

Key Temperature Points

Know these 1.2316 response points for proper heat treatment:

Ac1: 800-810°C — Austenite starts forming

Ac3: 883-910°C — Austenite change finishes

Ms: 200-235°C — Martensite starts

These temps change based on grain size evenness. Fine-grain ESR material has narrow change ranges. Coarse-grain standard steel has wider, hard-to-predict ranges. So you need to use safe heat treatment settings that hurt final properties.

Step-by-Step Heat Treatment

Top mills prep 1.2316 through controlled heat cycles before shipping. This sets up stable grain structure:

1. Forging range: 1050-850°C with 5:1 reduction ratio minimum. This breaks up casting grain structure. The mechanical work makes grains finer and removes weak directions.

2. Annealing: 770-820°C for 1 hour per 100mm thickness. Slow furnace cool to 250 HB max. This makes it soft and easy to machine. Proper annealing also evens out grain size through the whole billet.

3. Pre-hardening to 280-325 HB (29-33 HRC) gives you ready-to-cut stock with known properties. Some suppliers offer harder versions at 34-40 HRC for jobs needing less work after machining.

Hardening Response and CCT Data

The CCT (Continuous Cooling Transformation) chart shows how grain size affects hardening. Material heated to 1040°C has these key cooling rates:

- Above 800°C/hour: Full martensite forms (620 HV reached)

- 600°C/hour: Mixed martensite + bainite structure

- Below 300°C/hour: Pearlite forms, hardness drops below spec

Fine-grain material (size 6-8) handles wider cooling rate changes. You can air cool sections under 40mm. Coarse-grain steel needs oil quench even for thin sections to avoid soft spots.

Three-stage preheating stops thermal shock in complex mold shapes:

1. First stage: 550-650°C

2. Second stage: 800-850°C

3. Final heat: 1020-1050°C

Hold time is 1 hour per inch of cross-section. This full heat-soak makes sure grain structure changes completely before quench.

Size Control Through Proper Work

Thermal growth matters for tight-tolerance work. 1.2316 grows 10.3-11.9 × 10⁻⁶ per Kelvin based on temp range. Fine-grain material grows the same way every time. Uneven grain structure makes different zones grow at different speeds during heating.

Stress relief at 550-600°C after machining stops warping during final hardening. Skip this with poor-grain material? You’ll see twisting or bowing during quench.

Double temper at 180-200°C (first cycle) then 200-600°C (second cycle based on hardness needs). This locks in the martensite structure. Each temper cycle needs 2 hours minimum. Fine-grain material acts the same every time. Each temper drop gives exact hardness drop. Coarse-grain steel acts random during tempering.

Buyer’s Guide: Validating Premium 1.2316 Suppliers

1. Demand Full Traceability

Require mill certificates showing original origin, heat numbers, and the complete processing history. Ask for current client references in automotive or medical sectors.

2. Verify Production Route

Ensure the mill uses EAF + LF + VD as a baseline. Check refining logs for low sulfur/phosphorus (≤0.030%). For high-polish molds, strictly mandate ESR (Electroslag Remelting).

3. Audit Testing Reports (Non-Negotiable)

- Ultrasonic: Must meet SEP1921 or EN 10308 standards.

- Inclusions: ASTM E45 rating ≤1.0 (thick) and ≤1.5 (thin).

- Microstructure: ASTM E112 Grain Size ≥6.0; Class A carbide distribution.

- Hardness: Uniform 30-34 HRC across the cross-section.

4. Check Physical Delivery Standards

Specify six-sided milling with Ra <1.6 μm surface finish and flatness within 0.3mm/m to prevent rust. Ensure VCI moisture-barrier packaging is used for shipping.

Final Take: “I’ve seen enough toolmakers get blamed for bad polish or warping when the fault was already forged into the steel months ago. If your supplier can’t show you an ESR log or an ASTM E45 cleanliness report, they aren’t selling you tool steel—they’re selling you a gamble. At [FCS Tool Steel], we treat the steel’s DNA as our own reputation. Don’t gamble with your mold; choose documented integrity.”